C++ Audio Effect Acceleration - Verifying Object-Oriented Programming and SIMD with Assembly

This page has been translated by machine translation. View original

Introduction

When implementing audio effects in C++, prioritizing extensibility with a design using virtual can sometimes result in processing that is slower than expected, depending on how it's written. In this article, we'll compare the same processing in three ways: "per-sample", "block-based (with auto-vectorization)", and "block-based (manual AVX2)", and then examine why the measurement results were opposite to expectations using MSVC's auto-vectorization reports and assembly output (.cod). We'll clarify what to question, how to verify, and which optimizations actually work when trying to speed up audio processing while maintaining design integrity.

Background

In professional audio processing, applying multiple effects in a chain is common, and both of these requirements are needed:

- Effects should be easy to add or replace (maintainability, extensibility)

- Processing must be fast enough for real-time use (latency, CPU usage)

In this context, object-oriented programming (OOP) and SIMD optimization can work well together in some cases, but may not align depending on the implementation. This article aims to identify where this phenomenon occurs by analyzing measurement logs and generated code.

What is SIMD

SIMD is a mechanism that executes the same operation on multiple data points simultaneously, providing optimization that is particularly effective for operations like multiplication and min/max on continuous data such as float arrays (previous article on this topic). In C++, the compiler can automatically vectorize loops, or developers can explicitly write instructions using AVX2 and similar technologies.

Target Audience

- Those who have written simple DSP (gain/clip, etc.) in C++

- Those who understand sample-by-sample vs. block processing concepts but aren't confident about optimization verification

- Those who believe "hand-written SIMD (AVX2) should be faster" but have been disappointed by actual measurements

References

- FA, /Fa (Listing file)

- loop pragma (no_vector / ivdep, etc.)

- Vectorizer and parallelizer messages (C5001/C5002 and reason codes)

- Avoiding AVX-SSE Transition Penalties (Intel documentation)

Conditions for OOP and SIMD to Work Together

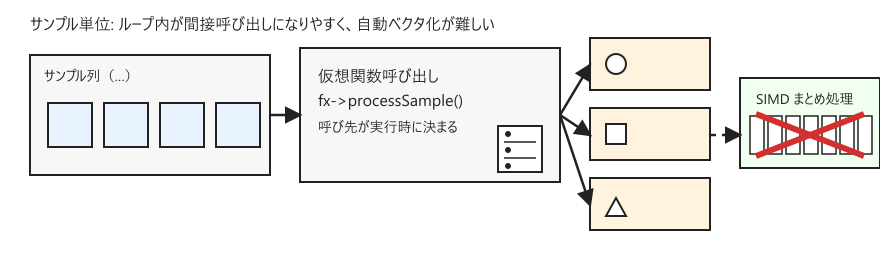

The Problem with virtual in Inner Loops

SIMD excels at repeating the same calculation on consecutive array elements. However, when virtual calls like fx->processSample(x) are made for each sample, indirect calls are likely to appear inside loops, making it difficult for the compiler to treat loops in a straightforward manner.

If we process in blocks (e.g., 512 samples at a time) instead of sample-by-sample, the virtual calls occur only once per block, and the inner loop that traverses the array can be a simple for loop. This form is more likely to benefit from the compiler's auto-vectorization, serving as a starting point for combining OOP and SIMD.

Test Environment

- CPU: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-11700F @ 2.50GHz

- Compiler: MSVC v143 (VS 2022 C++ x64/x86 build tools)

- Language mode: C++ 17

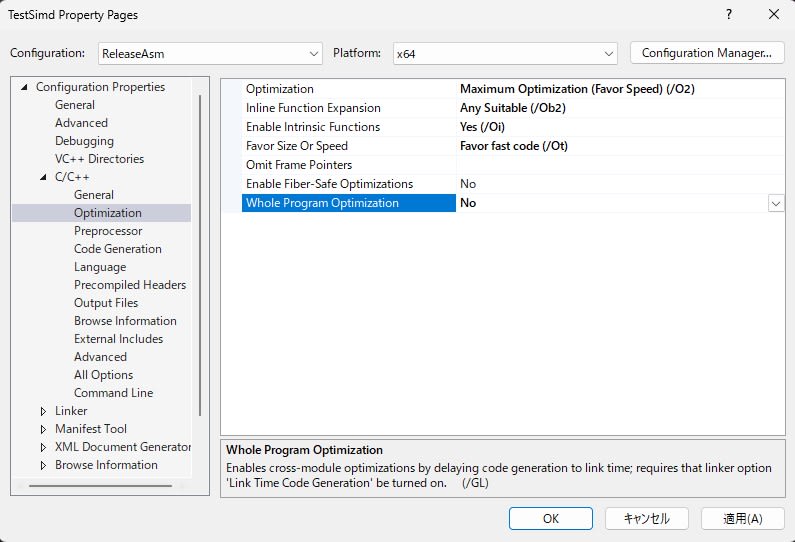

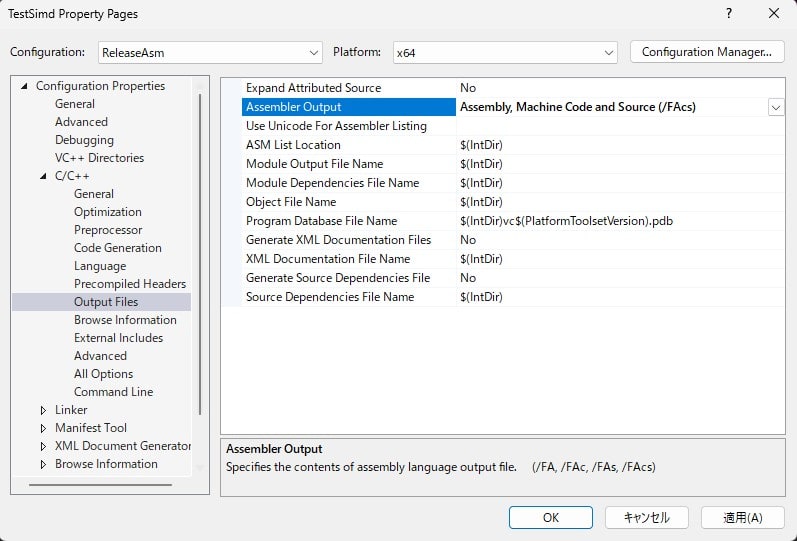

- Build configuration: ReleaseAsm x64

Compilation settings were adjusted to enable optimization while allowing verification of the generated code.

- Optimization:

/O2,/Ob2,/Oi,/Ot

- Instruction set:

/arch:AVX2 - Output:

/FAcs(listing with source-equivalent information and machine code)

Since our target is sample code, the absolute values will vary depending on the CPU generation and detailed options. Here, we're only concerned with confirming the relative trends between patterns.

Experiment Conditions

- Sample rate: 48kHz

- Block size: 512

- Total samples: 10,240,000 (512 × 20,000)

- Number of effects: 8 (applying gain and clip alternately)

- Measurement: Multiple runs under identical conditions, taking the fastest value

- Noise reduction: Raising thread priority and pinning to CPU core

Additionally, we output .cod using MSVC's /FAcs for verification purposes discussed later.

Test 1: Unexpected Results from A/B/C Measurements

We tested the following three patterns and measured their execution speed.

A: Calling virtual for Each Sample

A configuration where sample-based processSample() is called 8 times per sample. While extensible as OOP, the virtual call in the inner loop makes it difficult for the compiler to apply SIMD optimization.

sample-virtual code snippet

struct ISampleFx {

virtual ~ISampleFx() = default;

virtual float processSample(float x) noexcept = 0;

};

static BenchResult bench_sample_virtual(

const float* in, float* out, size_t nSamples, int chainLen, int repeats)

{

auto chain = make_sample_chain(chainLen);

for (int r = 0; r < repeats; ++r) {

float sum = 0.0f;

for (size_t i = 0; i < nSamples; ++i) {

float y = in[i];

for (auto& fx : chain) {

y = fx->processSample(y); // ← virtual for each sample

}

out[i] = y;

sum += y;

}

// timing / best-of-N omitted

}

}

B: virtual per Block, Simple for Inside Blocks

Push virtual calls to the block boundaries, with simple for loops for array traversal inside the blocks.

block-virtual scalar code snippet

struct IBlockFx {

virtual ~IBlockFx() = default;

virtual void processBlock(const float* in, float* out, int n) noexcept = 0;

};

struct GainBlockScalar : IBlockFx {

float g;

explicit GainBlockScalar(float gain) : g(gain) {}

void processBlock(const float* in, float* out, int n) noexcept override {

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

out[i] = in[i] * g; // ← simple loop (potential for auto-vectorization)

}

}

};

static BenchResult bench_block_virtual(

const float* in, float* out, size_t nSamples, int blockSize, int chainLen, /*...*/)

{

auto chain = make_block_chain(chainLen, /*useAvx2=*/false);

std::vector<float> scratchA(blockSize), scratchB(blockSize);

const size_t nBlocks = nSamples / (size_t)blockSize;

for (size_t b = 0; b < nBlocks; ++b) {

const float* curIn = in + b * (size_t)blockSize;

float* curOut = scratchA.data();

for (int i = 0; i < (int)chain.size(); ++i) {

chain[i]->processBlock(curIn, curOut, blockSize); // ← virtual per block

curIn = curOut;

curOut = (curOut == scratchA.data()) ? scratchB.data() : scratchA.data();

}

// writing to out (checksum addition omitted)

}

}

C: Manual AVX2 intrinsics Inside Blocks

Like B, virtual calls are placed at block boundaries, but the block internals process 8 elements at a time using intrinsics. This implementation uses loadu/storeu without assuming alignment.

block-virtual AVX2 code snippet

struct GainBlockAVX2 : IBlockFx {

float g;

explicit GainBlockAVX2(float gain) : g(gain) {}

void processBlock(const float* in, float* out, int n) noexcept override {

const __m256 vg = _mm256_set1_ps(g);

int i = 0;

for (; i + 8 <= n; i += 8) {

__m256 x = _mm256_loadu_ps(in + i);

__m256 y = _mm256_mul_ps(x, vg);

_mm256_storeu_ps(out + i, y);

}

for (; i < n; ++i) out[i] = in[i] * g; // tail

}

};

struct ClipBlockAVX2 : IBlockFx {

float lo, hi;

ClipBlockAVX2(float l, float h) : lo(l), hi(h) {}

void processBlock(const float* in, float* out, int n) noexcept override {

const __m256 vlo = _mm256_set1_ps(lo);

const __m256 vhi = _mm256_set1_ps(hi);

int i = 0;

for (; i + 8 <= n; i += 8) {

__m256 x = _mm256_loadu_ps(in + i);

x = _mm256_max_ps(x, vlo);

x = _mm256_min_ps(x, vhi);

_mm256_storeu_ps(out + i, x);

}

for (; i < n; ++i) { /* scalar tail */ }

}

};

The results were as follows:

A) sample-virtual 83.016 ms 123.35 MSamples/s

B) block-virtual scalar 6.675 ms 1534.15 MSamples/s

C) block-virtual AVX2 8.327 ms 1229.79 MSamples/s

There is significant improvement from A to B, clearly showing the effect of changing the virtual call placement (approximately 12.4x). However, B outperforms C, with manual AVX2 losing to B (which appears scalar in the source). At this point, the question shifts from "Is hand-written SIMD slow?" to "Was B really scalar?"

Compiler Report Investigation

The build log showed that the loops in B (GainBlockScalar / ClipBlockScalar) were classified as loop vectorized (C5001). This suggests that B might be effectively SIMD-optimized. Meanwhile, some parts of the AVX2 implementation were marked as not vectorized (C5002), indicating that writing manual SIMD code doesn't always align well with compiler optimizations.

However, reports are just hints, not conclusions. We need to examine the .cod to see what instructions are actually being generated.

Assembly Investigation

GainBlockScalar Is Using YMM-Width Multiplication

Checking the assembly for GainBlockScalar::processBlock, we can see that it's expanding coefficients into registers and multiplying 8 elements (YMM) at a time. Here's an excerpt from the relevant section:

; GainBlockScalar::processBlock (excerpt)

vbroadcastss ymm2, DWORD PTR [rcx+8]

...

vmulps ymm0, ymm2, YMMWORD PTR [rdi+rdx]

vmovups YMMWORD PTR [r8+rdx], ymm0

The presence of vmulps and YMMWORD PTR indicates that this loop is generated as 256-bit (float×8) width SIMD, at least in part. This means that while the source is scalar, the generated code is not.

ClipBlockScalar Also Uses YMM-Width min/max

Similarly, we can see vmaxps / vminps in ClipBlockScalar::processBlock:

; ClipBlockScalar::processBlock (excerpt)

vmaxps ymm0, ymm3, YMMWORD PTR [r11+rax-32]

vminps ymm0, ymm4, ymm0

vmovups YMMWORD PTR [r11+rax-32], ymm0

So far, regarding why "B is faster than C" in Test 1, it's highly likely that the assumption "B is a scalar implementation" is incorrect.

Test 2: Using no_vec to Make a Valid Comparison

B': Intentionally Disabling Auto-vectorization

In Test 2, we add #pragma loop(no_vector) to the inner loops of B's processBlock to suppress the compiler's auto-vectorization. This makes the comparison between B and C more valid as "scalar vs. hand-written SIMD".

block-virtual scalar(no_vec) code snippet

struct GainBlockScalarNoVec : IBlockFx {

float g;

explicit GainBlockScalarNoVec(float gain) : g(gain) {}

void processBlock(const float* in, float* out, int n) noexcept override {

#pragma loop(no_vector)

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

out[i] = in[i] * g;

}

}

};

struct ClipBlockScalarNoVec : IBlockFx {

float lo, hi;

ClipBlockScalarNoVec(float l, float h) : lo(l), hi(h) {}

void processBlock(const float* in, float* out, int n) noexcept override {

#pragma loop(no_vector)

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

float x = in[i];

if (x < lo) x = lo;

if (x > hi) x = hi;

out[i] = x;

}

}

};

We confirmed that pragma comments remained in the assembly at the relevant points:

; 128 : #pragma loop(no_vector)

; 129 : for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

The execution results were as follows:

A) sample-virtual 83.016 ms 123.35 MSamples/s

B) block-virtual scalar 6.675 ms 1534.15 MSamples/s

B') block-virtual scalar(no_vec) 27.504 ms 372.31 MSamples/s

C) block-virtual AVX2 8.327 ms 1229.79 MSamples/s

The significant slowdown from B to B' strongly suggests that B was benefiting from auto-vectorization. Also, C outperforms B', establishing a valid comparison of "hand-written SIMD superiority over scalar".

Assembly Verification: B' Uses Scalar Operations

Examining the .cod for B' with #pragma loop(no_vector), we can see that the main loop in GainBlockScalarNoVec::processBlock is generated as scalar instructions processing one element at a time. Here's an excerpt:

; GainBlockScalarNoVec::processBlock (excerpt)

; 128 : #pragma loop(no_vector)

vmovss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rdi+rdx]

vmulss xmm0, xmm0, DWORD PTR [rcx+8]

vmovss DWORD PTR [r8+rdx], xmm0

The vmulss instruction here is a scalar multiplication (1 element) using XMM registers, which is different from vmulps that calculates with YMM width (8 elements). This confirms that B' has "fallen back" to scalar not just in appearance but in the generated code as well.

Similarly, in ClipBlockScalarNoVec::processBlock, we can see scalar instructions like vmaxss / vminss:

; ClipBlockScalarNoVec::processBlock (excerpt)

; 137 : #pragma loop(no_vector)

vmovss xmm0, DWORD PTR [r11+rax-4]

vmaxss xmm1, xmm0, DWORD PTR [rcx+8]

vminss xmm2, xmm1, DWORD PTR [rcx+12]

vmovss DWORD PTR [rax-20], xmm2

From the above, the main reason B was fast in Test 1 is that even though the source was scalar, it was actually generating SIMD instructions (YMM width) through auto-vectorization. The comparison of B and C in Test 1 wasn't "scalar vs. hand-written AVX2" but actually "auto-vectorized implementation vs. hand-written AVX2 implementation".

Under these conditions, the hand-written AVX2 version can become more complex due to tail processing and alignment optimization constraints with loadu/storeu, which can result in the auto-vectorized code being better in terms of unrolling and scheduling, leading to a performance gap of around 25%. Therefore, it's inappropriate to conclude that "hand-written SIMD is meaningless" based solely on C's inferiority to B. In comparative experiments, we need to establish "what we're comparing with what" based not on implementations but on generated code before making an evaluation.

Discussion

The Starting Point for Optimization Is Not "Writing SIMD" But "Arranging Code So SIMD Works"

As A → B shows, simply pushing virtual calls to block boundaries and making inner loops into simple array traversals can change performance by an order of magnitude. In practice, reorganizing the processing structure is more effective than hand-written instructions.

Scalar Implementation Is Not Necessarily Scalar in Practice

As shown by the results of B and B', the compiler will auto-vectorize in optimized builds. Without understanding "what the generated code actually is," conclusions can be reversed in comparative experiments. In this article, we used compiler reports as clues and verified with assembly output to determine what we were actually comparing.

Conclusion

In this article, we analyzed the "measurement inversion" that often occurs when trying to combine OOP and SIMD, using measurement results, compiler reports, and assembly output as evidence. The conclusion is that B (block-virtual scalar) was fast because the generated code was SIMD-optimized even though the source was scalar, and when auto-vectorization was disabled in B', C (hand-written AVX2) became superior. In practice, it's safer to first "blockify and simplify loops" to maximize compiler optimization, and then consider hand-written SIMD only if necessary.