What is SIMD - Trying to Speed up Audio Buffer Gain Processing in C++

This page has been translated by machine translation. View original

Introduction

In this article, we will review the basics of SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data), which is frequently mentioned when writing audio processing code in C++, and check how much processing speed actually changes through a simple benchmark. Using a simple process of "applying gain to an entire buffer" as our subject, we'll also observe how behavior changes with different compilation options.

Target Audience

- Those who write audio processing applications in C++

- Those who have heard of SIMD but want to get a better sense of how much faster it actually makes things

References

- /O options (Optimize Code) - Visual Studio / MSVC C++

- /arch (x64) - Enable Extended Instruction Set

- Intel® Intrinsics Guide

- SIMD Introduction (C Language SIMD Introduction: Table of Contents)

- Intro to practical SIMD for graphics

What is SIMD?

Why is it well-suited for audio processing?

In real-time audio processing, there are many operations that repeat the same calculation for all samples in a buffer. Typical examples include:

- Applying a constant gain to an audio buffer

- Adding multiple tracks together for mixing

- Multiplying envelope or filter coefficients to all samples

When written straightforwardly in C++, this typically becomes a for loop like the following:

// Scalar version of gain processing

void applyGainScalar(float* buffer, size_t n, float gain) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

buffer[i] *= gain;

}

}

In this case, the CPU conceptually processes 1 sample per loop iteration. It reads one value from memory, multiplies it, and writes one result back - repeating this process for each sample.

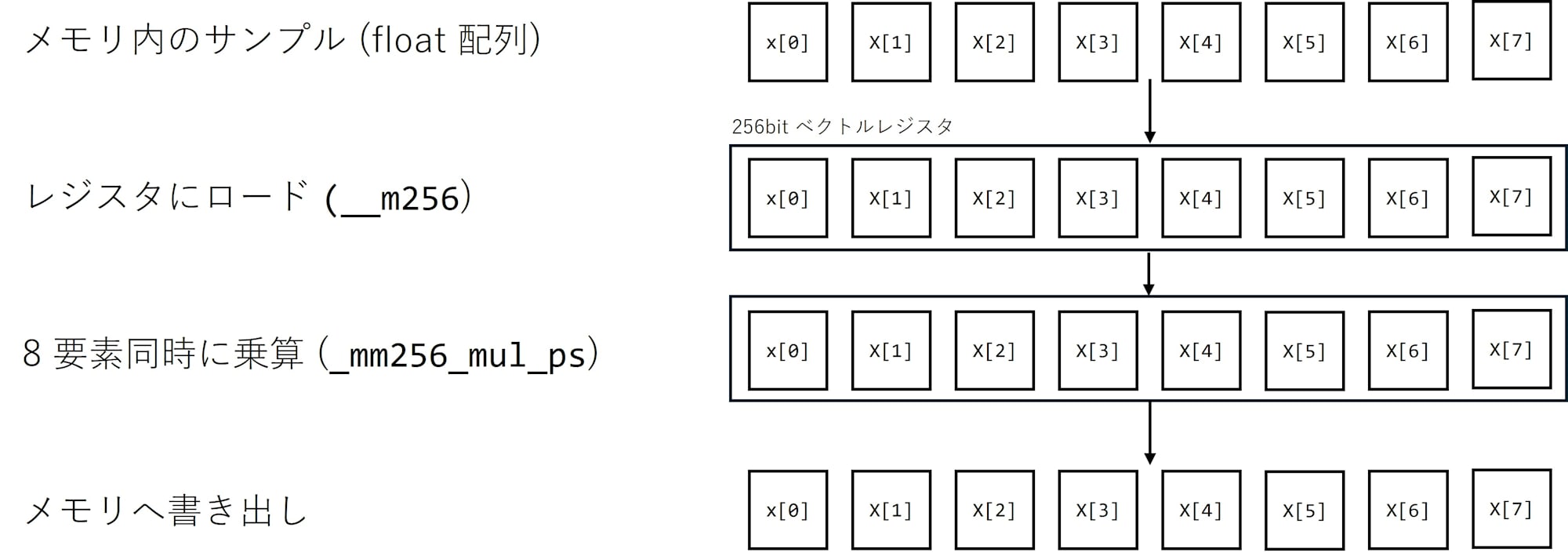

SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) breaks this "1 instruction for 1 data" premise and provides a mechanism to process multiple data points with a single instruction. The CPU contains vector registers with widths of 128 bits or 256 bits that can hold multiple 32-bit float values (4 or 8 values) in a single register and perform addition or multiplication on all of them at once. For example, with AVX2's 256-bit registers, you can handle 8 32-bit floats at once, meaning you can perform multiplication on 8 samples simultaneously with a single instruction.

How to use SIMD

There are two main approaches to using SIMD in C++:

-

Let the compiler optimize for you

Write a straightforward for loop and enable optimization options like/O2or/Ot. The compiler will automatically vectorize loops that meet certain conditions. Modern compilers are quite smart and will often replace your code with SSE/AVX instructions without you having to think about it. -

Explicitly call vector instructions using intrinsic functions

Include headers like#include <immintrin.h>and use functions such as_mm256_set1_ps,_mm256_mul_ps, and_mm256_loadu_psto explicitly load, multiply, and write back 8 elements at once.

In this article, as an example of the latter approach, we'll write gain processing using AVX2 as follows:

#include <immintrin.h>

// Example of applying gain to 8 samples at a time using AVX2

void applyGainAvx(float* buffer, size_t n, float gain) {

__m256 g = _mm256_set1_ps(gain); // Expand gain to an 8-element vector

size_t i = 0;

size_t simdN = n & ~size_t(7); // Round down to a multiple of 8

for (; i < simdN; i += 8) {

__m256 x = _mm256_loadu_ps(&buffer[i]); // Load 8 samples

__m256 y = _mm256_mul_ps(x, g); // Multiply 8 samples simultaneously

_mm256_storeu_ps(&buffer[i], y); // Store back

}

// Process the remainder with scalar code

for (; i < n; ++i) {

buffer[i] *= gain;

}

}

The code becomes somewhat harder to read, but the advantage is that we can explicitly state "this loop always uses AVX2". Loops that perform the same calculation on all samples in a continuous array, which is common in audio processing, are very well-suited for SIMD.

Actual Measurements

Benchmark Conditions

Now, let's use the applyGainScalar and applyGainAvx functions from earlier to measure how much the processing time actually changes.

The benchmark conditions are as follows:

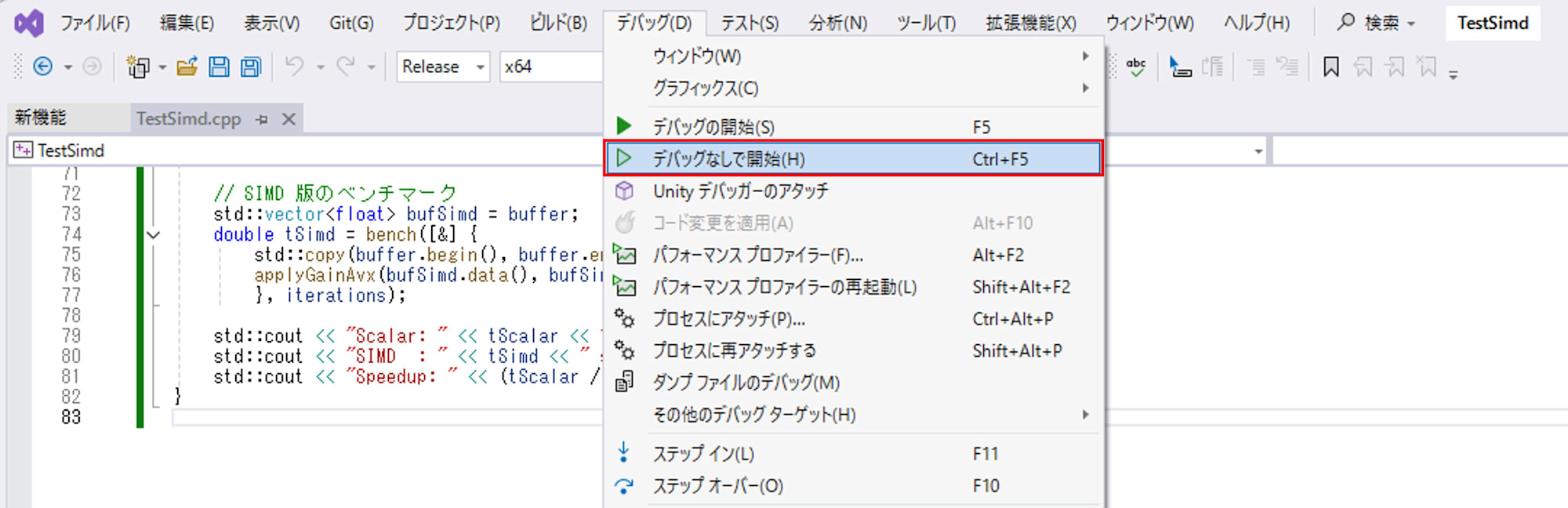

- Compiler/IDE: Visual Studio 2022 / MSVC

- Build Configuration: Release / x64

- Execution Method: "Start Without Debugging" (Ctrl + F5)

- Number of Samples: 1,048,576 samples (

1 << 20) - Loop Count: Each implementation repeated 200 times

- Gain Value:

0.5f

Benchmark Code

#include <immintrin.h>

#include <chrono>

#include <functional>

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

#include <algorithm>

// Scalar version

void applyGainScalar(float* buffer, size_t n, float gain) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

buffer[i] *= gain;

}

}

// SIMD version (AVX2)

void applyGainAvx(float* buffer, size_t n, float gain) {

__m256 g = _mm256_set1_ps(gain);

size_t i = 0;

size_t simdN = n & ~size_t(7); // Round down to a multiple of 8

for (; i < simdN; i += 8) {

__m256 x = _mm256_loadu_ps(&buffer[i]);

__m256 y = _mm256_mul_ps(x, g);

_mm256_storeu_ps(&buffer[i], y);

}

for (; i < n; ++i) {

buffer[i] *= gain;

}

}

// Benchmark helper

double bench(const std::function<void()>& f, int iterations) {

using clock = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock;

// Warmup

for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) {

f();

}

auto start = clock::now();

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; ++i) {

f();

}

auto end = clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> diff = end - start;

return diff.count();

}

int main() {

const size_t N = 1 << 20; // 1M samples

const int iterations = 200;

const float gain = 0.5f;

std::vector<float> buffer(N);

// Fill with random numbers

std::mt19937 rng(12345);

std::uniform_real_distribution<float> dist(-1.0f, 1.0f);

for (auto& v : buffer) {

v = dist(rng);

}

// Scalar benchmark (reset buffer each time)

std::vector<float> bufScalar = buffer;

double tScalar = bench([&] {

std::copy(buffer.begin(), buffer.end(), bufScalar.begin());

applyGainScalar(bufScalar.data(), bufScalar.size(), gain);

}, iterations);

// SIMD benchmark

std::vector<float> bufSimd = buffer;

double tSimd = bench([&] {

std::copy(buffer.begin(), buffer.end(), bufSimd.begin());

applyGainAvx(bufSimd.data(), bufSimd.size(), gain);

}, iterations);

std::cout << "Scalar: " << tScalar << " sec" << std::endl;

std::cout << "SIMD : " << tSimd << " sec" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Speedup: " << (tScalar / tSimd) << "x" << std::endl;

}

Here, we copy from buffer to bufScalar / bufSimd each time before running the processing. This ensures that both the scalar and SIMD versions process exactly the same input data, and also helps to somewhat avoid biasing cache states based on processing order. This isn't a rigorous benchmark, but it's sufficient to see the general trends.

We compared the following two compilation option patterns:

- No code optimization:

/OdAll options

/permissive- /ifcOutput "TestSimd\x64\Release\" /GS /GL /W3 /Gy /Zc:wchar_t /Zi /Gm- /Od /Ob2 /sdl /Fd"TestSimd\x64\Release\vc143.pdb" /Zc:inline /fp:precise /D "NDEBUG" /D "_CONSOLE" /D "_UNICODE" /D "UNICODE" /errorReport:prompt /WX- /Zc:forScope /arch:AVX2 /Gd /Oi /MD /FC /Fa"TestSimd\x64\Release\" /EHsc /nologo /Fo"TestSimd\x64\Release\" /Ot /Fp"TestSimd\x64\Release\TestSimd.pch" /diagnostics:column - Maximum speed priority:

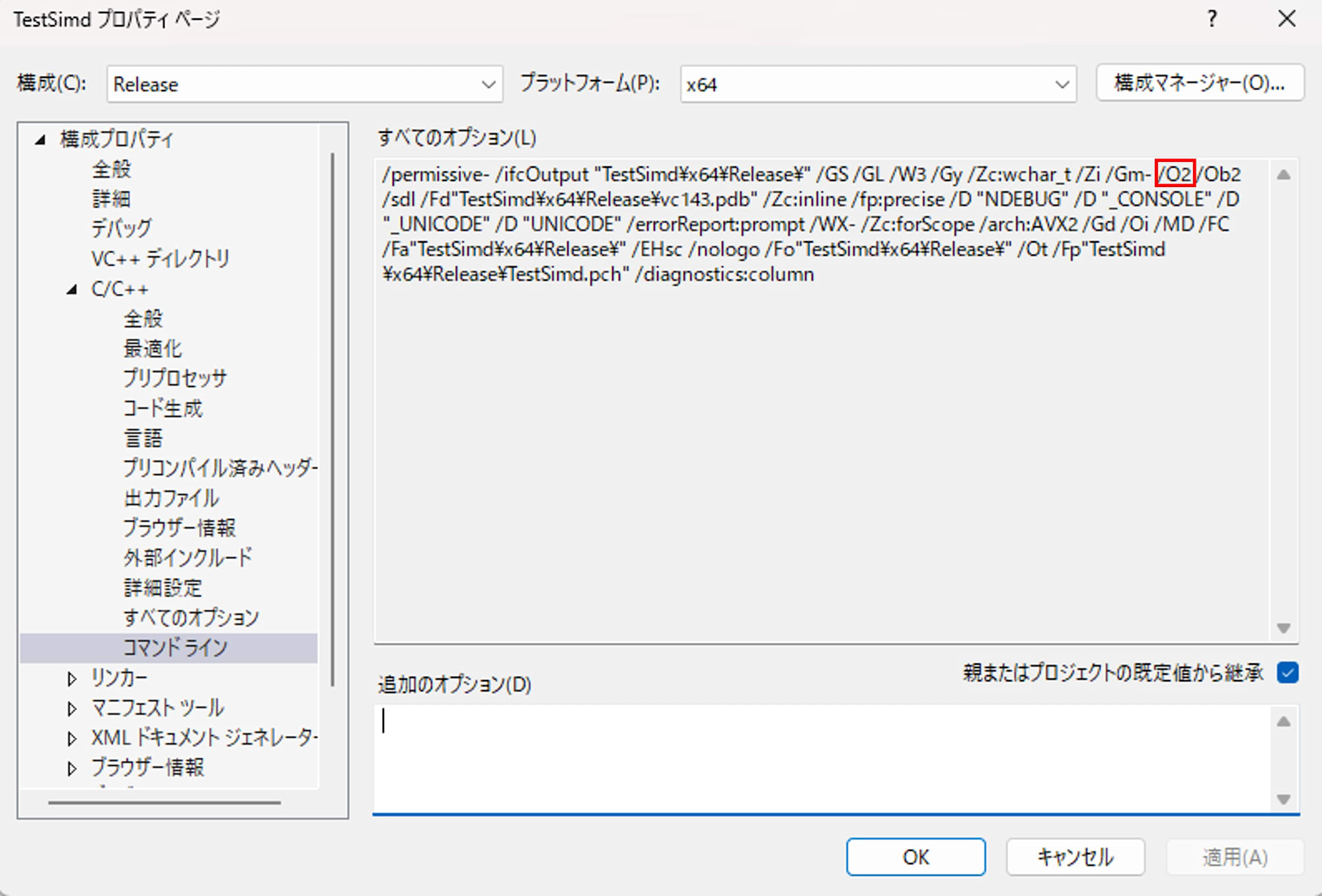

/O2All options

/permissive- /ifcOutput "TestSimd\x64\Release\" /GS /GL /W3 /Gy /Zc:wchar_t /Zi /Gm- /O2 /Ob2 /sdl /Fd"TestSimd\x64\Release\vc143.pdb" /Zc:inline /fp:precise /D "NDEBUG" /D "_CONSOLE" /D "_UNICODE" /D "UNICODE" /errorReport:prompt /WX- /Zc:forScope /arch:AVX2 /Gd /Oi /MD /FC /Fa"TestSimd\x64\Release\" /EHsc /nologo /Fo"TestSimd\x64\Release\" /Ot /Fp"TestSimd\x64\Release\TestSimd.pch" /diagnostics:column

Both use the "Configuration: Release / x64" settings, with only the optimization level being switched for measurement.

Measurement Results and Interpretation

| Optimization option | Scalar time [s] | SIMD time [s] | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

/Od |

0.295703 | 0.109595 | 2.70x |

/O2 |

0.077822 | 0.067121 | 1.16x |

With the /Od option that disables code optimization, the scalar implementation truly processes "one sample at a time in sequence," while only the SIMD implementation processes 8 samples at a time using AVX2. As a result, we observed an approximately 2.7x speed difference, which matches our expectations.

On the other hand, with /O2 enabling optimization, the scalar implementation's loop also becomes subject to the compiler's automatic vectorization. Since we specified /arch:AVX2, the compiler can freely use AVX2 instructions and will automatically replace simple loops with vector instructions like vmulps. As a result, the machine code for both scalar and handwritten SIMD implementations becomes quite similar, and the difference between them shrinks to about 1.16x. The cost of std::copy (memory copy) performed in the benchmark affects both implementations equally, so the relative difference in gain computation itself becomes smaller within the overall processing time.

From these two patterns, we can understand the following:

- SIMD itself can be expected to provide a 2-3x improvement even without optimization

- In Release builds, the compiler performs aggressive vectorization, so the additional effect of handwritten SIMD may not be as dramatic

- In practical projects, a reasonable approach is to "first write straightforward C++ code, rely on optimization and auto-vectorization, and only consider handwritten SIMD for hot spots that are still performance bottlenecks"

Conclusion

In this article, we've reviewed the basic concepts of SIMD and confirmed how much speed actually changes through a simple benchmark of gain processing. While we saw a 2-3x difference without optimization, in Release builds the compiler automatically vectorizes code, which can reduce the additional benefit of handwritten SIMD to around 10% in some cases.

In practice, it seems appropriate to first write straightforward loops, profile them, and only carefully tune with SIMD for parts that are genuinely bottlenecks.