Why I, a Game Engineer, Was Captivated by Twilio

This page has been translated by machine translation. View original

Introduction

Since starting my career as a game developer, technologies like phone calls and SMS have been completely unfamiliar territory for me. They are primarily used in the context of business applications and customer support, and there's rarely an opportunity to work with them in game development, which focuses on real-time presentation and interaction. The specifications seemed complicated, and above all, I felt a certain physical and institutional weight in processes like "acquiring a number" or "sending messages."

I honestly didn't want to get involved in such areas. Compared to designing Web APIs or real-time UI control, phone calls and SMS seemed heavy in operation, difficult to control, and somehow not an extension of my own code.

That's when I encountered Twilio, a communication API service. Sending SMS, initiating automated voice calls... I remember feeling both amazed and uncomfortable that such functions could be handled in a web context. It was a strange experience, as if a technology I thought was far away suddenly became something accessible and prominent.

In this article, I'll explore why I, as a game engineer, was attracted to Twilio, and the change in thinking behind it. Rather than providing a technical introduction or instruction manual, I want to write about Twilio's unexpected possibilities from the perspective of "why this API seemed interesting in the context of games."

Technical Background as a Game Engineer

Until now, I've been involved mainly with sound-related engineering in game development. In the audio domain, we handle 48,000 samples per second. The actual processing is updated every 1/60 second in units of hundreds of samples, and even a single processing delay is immediately reflected in the user experience as noise or audio dropouts. For these reasons, very high precision is required for processing efficiency and response speed, and I've sometimes made detailed adjustments, such as reading assembly code to reduce memory by a few bytes for optimization.

In such an environment, "seeing where and what is happening" is a fundamental premise. Designing to grasp the overall picture of control and making fine adjustments to ensure it works as intended. A technical system that can be completed within my own hands was my standard for development.

That's why communication methods like phone calls and SMS were distant both technically and conceptually. I felt that there was little room for my code to intervene in this area involving telecommunication carriers, systems, physical infrastructure, and various other factors. What goes where and how. Unlike Web APIs, I honestly felt a distance from the invisible world behind the mechanism.

(However, if you think about it, the era when telephone lines were physically connected might have had simpler and more immediate operations. As they have been abstracted as APIs and made controllable from the web, flexibility has increased, but it has become less visible where and what the processes are doing.)

What made Twilio fresh for me was that I felt my code could enter into this "area beyond control." It was a technology that gave me the sense that I could reach out from a web developer's perspective into an area I had avoided or thought was irrelevant.

Writing a Switchboard Operator's Job with Webhooks

What was particularly impressive about Twilio was the system of "controlling phone calls with webhooks."

For example, when a call comes in to a certain phone number, Twilio sends an HTTP request to a pre-specified URL. By returning a response using TwiML, an XML-based notation, to that request, you can instruct it to "first play a synthesized voice announcement," "have the caller press a number to branch," or "transfer to another number."

When I learned about this structure, I was reminded of telephone switchboard operators of the past. From the era when lines were manually switched with phrases like "connecting you from Mr. X to Ms. Y" (although it's now incomparably more automated), the essence of the problem—how to connect whom to whom—might not have changed.

Of course, the approach is fundamentally different. Phone calls immediately arrive as HTTP requests, and the flow of the call is determined by the response... in other words, you can determine the phone route with code on the spot. In the world of game development, this is similar to event-driven logic where "a certain input triggers a reaction you can design." The interesting thing about Twilio is that the output is not a screen but an actual voice call.

Twilio has transformed the phone system from "communication infrastructure" to "development target." Both the simplicity of the structure and the real-world weight behind it were new surprises for me.

Attempts and Limitations of Utilizing Twilio in Games

When I learned that phones and SMS could be operated from code using Twilio, I naturally thought, "What would happen if I incorporated this into games?" For example, I thought that experiences like receiving a phone call from a character at a certain moment in the story, or getting response choices via SMS, could create a sensation where the player's real space and the game world blend together.

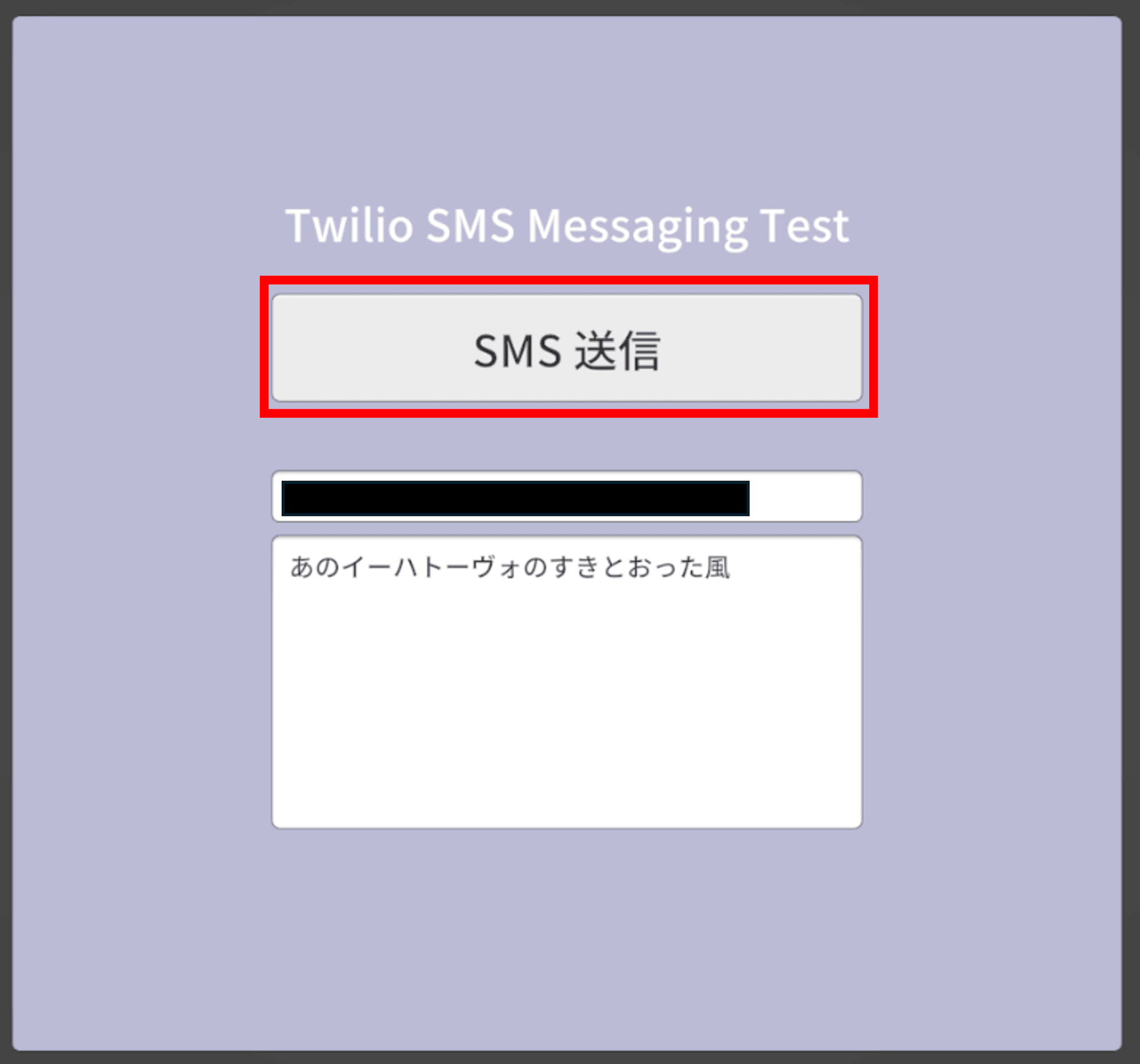

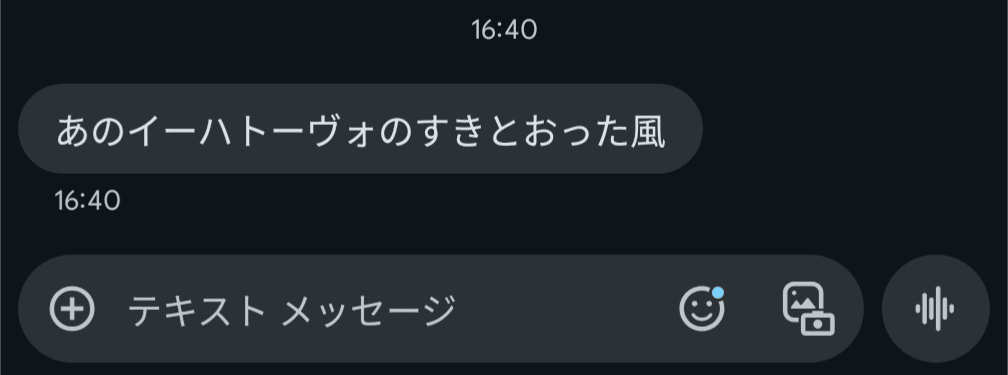

I actually conducted a test sending SMS from a Unity application using Twilio. The mechanism of delivering messages to a real smartphone in response to in-game events had a realism that seemed to affect the world outside the player. Currently still in the verification stage, I'm continuing to develop concepts for interactive dialogue experiences combining voice calls as well.

Unity UI: Pressing the button sends an SMS

Test message sent to smartphone

On the other hand, such "blending game experiences" come with practical constraints. First, there's the cost of communication itself. While Twilio's API is very easy to use, SMS and calls use actual communication infrastructure, so usage-based billing occurs, including for tests. Unlike typical digital games that can be played repeatedly for free, careful consideration is required for repeated operation tests and designs premised on many users.

There are also high hurdles in UX and privacy design for obtaining players' phone numbers. How to handle phone numbers as personal information, how to obtain user consent, when to deliver notifications... these elements require thinking that is closer to the context of SaaS or business applications rather than games.

Another challenge is the strong dependence on environmental factors that vary by user, such as device settings, communication status, and OS specifications. Unlike experiences that are completed entirely within an app, player environments are difficult to predict, which can limit design freedom.

However, these constraints are not necessarily negative. Rather, it seems that the special appeal of experiences using Twilio comes from the distance that cannot be easily bridged. For example, if instead of building an entire game with Twilio, we use it to create a moment where reality connects at just one point in the story, I think we can maximize the reality of communication without compromising design freedom as a game.

This technology may still be experimental material for games. But in contexts that extend player sensations, like horror or alternate reality games, I believe Twilio's characteristics can be a unique weapon.

Conclusion

In this article, I've written about how I encountered the communication API Twilio from the perspective of a game developer and how I perceived its possibilities. Games often aim to make fictional worlds "feel real." If we can create moments where fiction leaks into reality through technologies like Twilio, it might generate an immersive experience unlike any before. Communication infrastructure is not just a pathway for data but can become part of the story... I hope such a perspective can be a hint for someone's creative work.