I created a browser FPS game using Next.js and Three.js and deployed it to Vercel

This page has been translated by machine translation. View original

Introduction

"How far can an FPS (First Person Shooter) experience be achieved in a browser?"

To test this question, I created a browser FPS game using Next.js and Three.js, and deployed it to Vercel.

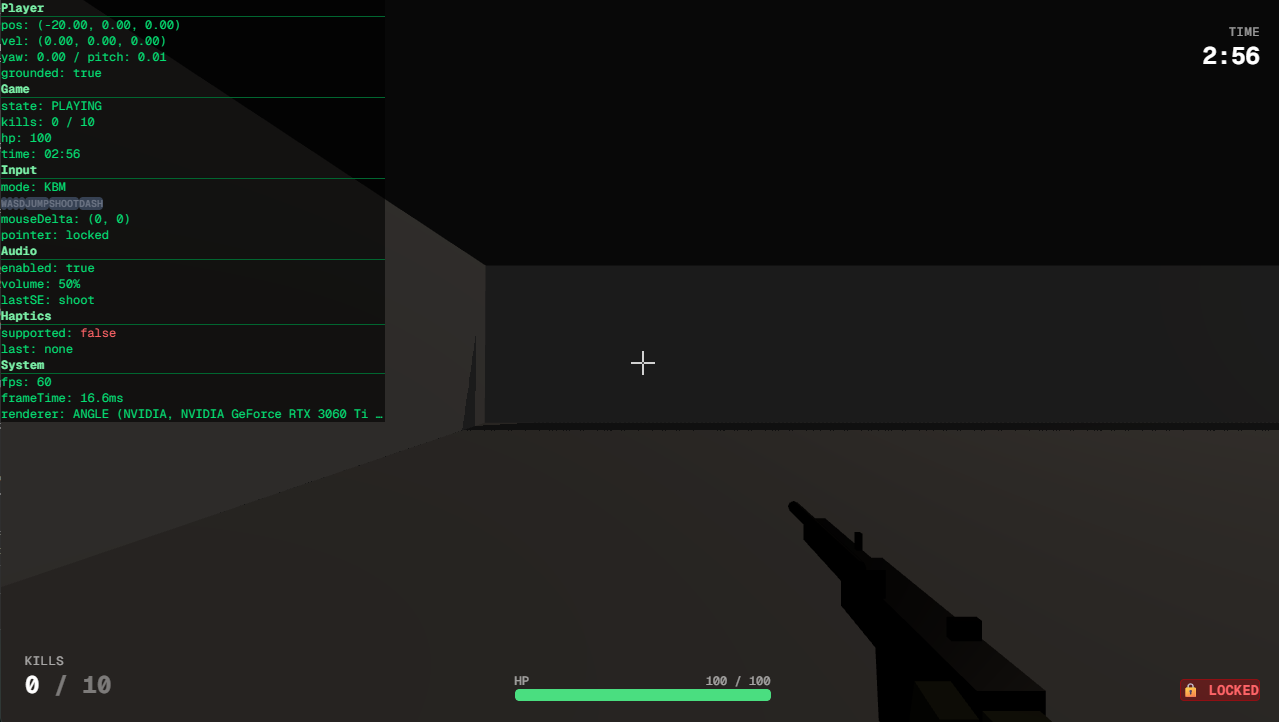

In an underground facility-style stage, you must defeat 10 zombies.

After defeating them, proceed through the opened door to clear the game.

In this article, I'll introduce the design considerations of this game - "separation of game engine layer and React" - and insights gained from Vercel deployment.

What is Vercel

Vercel is a cloud platform for frontend applications provided by the developers of Next.js. It integrates with Git repositories and automatically handles building and global CDN distribution with just a push.

Target Audience

- Frontend engineers interested in Three.js or 3D graphics in browsers

- Those who want to incorporate real-time rendering in React-based applications

- Those who want to deploy non-typical applications like games using Next.js + Vercel

References

- Three.js Official Documentation

- Zustand GitHub Repository

- Pointer Lock API - Web API | MDN

- Web Audio API - Web API | MDN

Technology Stack

| Category | Technology |

|---|---|

| Framework | Next.js 16 (App Router) |

| Language | TypeScript (strict) |

| 3D Rendering | Three.js |

| State Management | Zustand |

| CSS | Tailwind CSS 4 |

| Deployment | Vercel |

Although @react-three/fiber (R3F) was an option as a wrapper library for Three.js, I chose to use Three.js directly. The reason relates to the architecture explained in the next section.

Separation of Game Engine and React

FPS games require a "game loop" that repeatedly processes input, updates game logic, and renders every frame. Conversely, React's rendering cycle runs asynchronously in response to state changes. Mixing these two can cause frame drops and state inconsistencies.

To address this issue, I adopted a three-layer architecture where the game engine is completely separated from React, with Zustand store as the only bridge.

Engine Layer: Pure TypeScript Independent of React

The game engine layer is a collection of pure TypeScript modules in the src/game/ directory. It does not use React APIs.

The Engine class manages the game loop and updates each subsystem every frame.

private update(timestamp: number): void {

const rawDt = (timestamp - this.lastTime) / 1000;

const dt = Math.min(rawDt, GAME.DT_CAP);

this.lastTime = timestamp;

const input = this.inputManager.poll();

const store = useGameStore.getState();

if (store.game.state === 'PLAYING' && !store.game.paused) {

this.player.update(dt, input);

// ... shooting, enemy updates, physics checks, game progress check

}

this.syncStore(dt);

this.renderer.render(this.scene, this.camera);

this.animationFrameId = requestAnimationFrame((t) => this.update(t));

}

Interaction with the store is limited to synchronous reads via getState() and writes via setState(). It is unaffected by React's useEffect or useState, ensuring the game loop doesn't impact React's rendering cycle.

Store Layer: Single Shared State with Zustand

The store layer is a single Zustand store that manages game state, player information, input data, effect states, and more.

export const useGameStore = create<GameStoreState>((set) => ({

game: {

state: 'READY',

kills: 0,

hp: PLAYER.MAX_HP,

timeRemaining: GAME.TIME_LIMIT,

doorState: 'LOCKED',

paused: false,

// ...

},

player: { position: { x: 0, y: 0, z: 0 }, velocity: { x: 0, y: 0, z: 0 }, /* ... */ },

input: { mode: 'KBM', pointerLocked: false, /* ... */ },

effects: { damageFlash: 0, hitMarker: null, muzzleFlash: 0 },

// ...

}));

The engine layer writes values needed for UI display (player coordinates, FPS information, etc.) to the store every frame using syncStore(). Since setState() runs every frame, the React side uses selectors to subscribe only to necessary values and suppresses unnecessary re-rendering.

High-frequency update values like coordinates are only referenced in the debug HUD, which is normally hidden during regular play, so they don't contribute to rendering load.

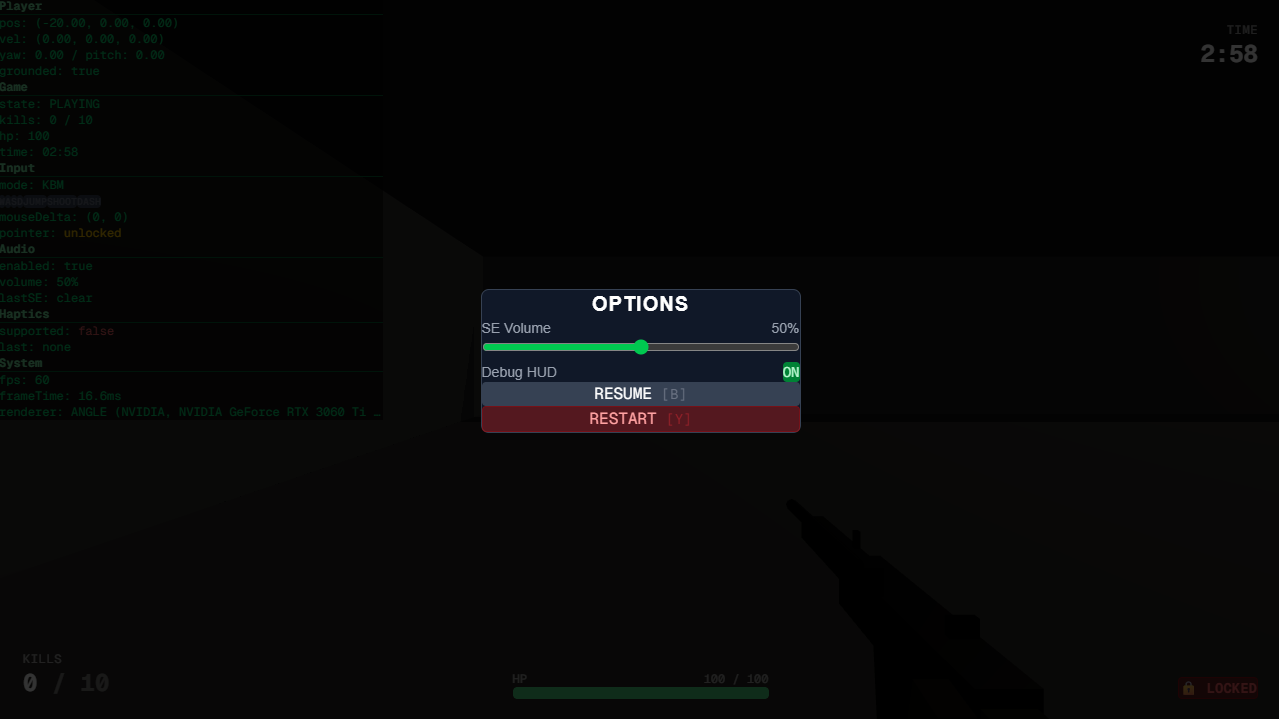

Debug HUD can be toggled in options

Actual debug HUD

UI Layer: Display-Only React Components

The UI layer only displays store values and contains no game logic.

export default function GamePage() {

return (

<main className="relative w-screen h-screen overflow-hidden bg-black">

<GameCanvas /> {/* z-0: Three.js canvas */}

<HUD /> {/* z-10: Kills, HP, remaining time */}

<DamageOverlay /> {/* z-10: Red vignette when hit */}

<HitMarker /> {/* z-10: Hit marker */}

<DebugHUD /> {/* z-20: Debug information */}

<ReadyScreen /> {/* z-30: Start screen */}

<ClearScreen /> {/* z-30: Clear screen */}

<FailedScreen /> {/* z-30: Failure screen */}

<OptionsMenu /> {/* z-40: Options menu */}

</main>

);

}

It's a simple structure with HUD and menus layered on top of the Three.js canvas using z-index. The GameCanvas component creates and starts the Engine in useEffect and disposes of it on unmount.

export default function GameCanvas() {

const containerRef = useRef<HTMLDivElement>(null);

const engineRef = useRef<Engine | null>(null);

useEffect(() => {

if (!containerRef.current || engineRef.current) return;

const engine = new Engine();

engine.init(containerRef.current);

engine.start();

engineRef.current = engine;

return () => {

engine.stop();

engine.dispose();

engineRef.current = null;

};

}, []);

return <div ref={containerRef} className="absolute inset-0 z-0" />;

}

React is only responsible for managing the Engine's lifecycle and is not involved in the game loop inside the Engine.

Insights from Vercel Deployment

Considerations for Next.js + Three.js Combination

Three.js depends on window and document, so it doesn't work directly in Next.js's SSR (Server-Side Rendering) environment. I addressed this by declaring the GameCanvas component as a Client Component using the 'use client' directive, and initializing the Engine only within useEffect.

'use client';

import { useEffect, useRef } from 'react';

import { Engine } from '@/game/engine';

export default function GameCanvas() {

useEffect(() => {

// Engine initialization only occurs on the client side

const engine = new Engine();

engine.init(containerRef.current);

engine.start();

// ...

}, []);

}

Since Three.js itself is imported within the Engine module, it worked without needing dynamic imports via next/dynamic. This is because the browser environment is guaranteed by the time it's called from the Client Component's useEffect.

Build Results and Distribution

In the Next.js build, all pages were output as static pages.

Route (app)

┌ ○ /

└ ○ /_not-found

○ (Static) prerendered as static content

Since all game logic runs in client-side JavaScript, server-side processing is unnecessary. Vercel distributes build artifacts globally via CDN, providing fast initial loading from any region.

In this build log, the build completed in about 24 seconds. Installing dependencies including Three.js took about 12 seconds, and the Next.js build itself took about 11 seconds. These are reference values as build machine specifications vary with plans and settings.

Actual Play Experience

When playing the game deployed to Vercel, there were no noticeable processing drops or stutters, and the experience was equivalent to local development. The frame rate remained stable even with 10 enemies moving on screen simultaneously, and there was no delay in shooting or hit detection responses.

This is because all game logic is contained client-side with no server communication. Vercel's role is limited to static file delivery, so runtime performance depends solely on the user's browser and device. Conversely, this means device specifications directly impact the play experience, so separate testing is necessary for mobile devices and low-spec machines.

Pointer Lock API Constraints

FPS games use the Pointer Lock API to hide the mouse cursor and obtain relative mouse movement. A browser-specific constraint emerged: immediately after a user cancels Pointer Lock with the Esc key, some browsers may block subsequent requestPointerLock() calls.

This constraint caused issues when trying to re-acquire Pointer Lock after pausing with Esc and then unpausing. As a solution, I removed requestPointerLock() calls from the Esc key handler and switched to re-acquiring through canvas click events.

// Re-acquire Pointer Lock on canvas click

this.onCanvasClick = () => {

const game = useGameStore.getState().game;

if (game.state === 'PLAYING' && !game.paused && !document.pointerLockElement) {

this.requestPointerLock();

}

};

canvas.addEventListener('click', this.onCanvasClick);

While Pointer Lock is released, the HUD displays "CLICK TO RESUME" to prompt the player to click.

Conclusion

With Next.js + Three.js + Zustand, I was able to build an FPS experience that is fully playable in the browser.

From a design perspective, the three-layer architecture that completely separates the game engine from React, with Zustand as the sole interface, was effective. This avoids conflicts between the game loop and React rendering cycle while still leveraging React's convenience for implementing HUD and menus.

For Vercel deployment, delivering the game as static pages provided fast initial loading, but handling browser-specific constraints like the Pointer Lock API required attention.

Whether to use Three.js directly or R3F for browser game development depends on the project's nature. For genres with high real-time requirements like FPS, direct usage that allows control over the game loop seemed more appropriate.